Nachbarschafts

akademi

The Nachbarschaftsakademie (NAK, 2015-2019) was created as a self-organized platform for collective learning, bringing together critical artistic practices and urban and rural activism. The NAK was an educational project with base in Prinzessinnengarten by Moritzplatz, bound up with an ecosystem of other projects that share similar goals – guiding an eco-social practice over time.

Growing From the Ruins of Modernity

Program 2019The global ecological crisis and its social repercussions raise questions also about new forms of education. Which kind of future are we learning for – a future in which we share the responsibility for life on this planet or a future of accelerated destruction? In 2015 the ›Nachbarschaftsakademie‹ began experimenting with self-organised forms of learning, between activism and art. In summer 2019, under the title Growing From the Ruins of Modernity, a curriculum for a permanent place of life-long learning will be developed – for the next 99 years – at the community garden in Kreuzberg. Learning, in our book, means contributing collectively and joyfully to forms of co-existence in which human beings and the biosphere are not exploited.

Marco Claussen and Åsa Sonjasdotter

in EVERYTHING GARDENS!

GROWING FROM THE RUINS OF MODERNITY.

Ed. Herbst, Marc and Teran, Michelle. Adocs. 2019.

Graphic design by Luca Bogoni.

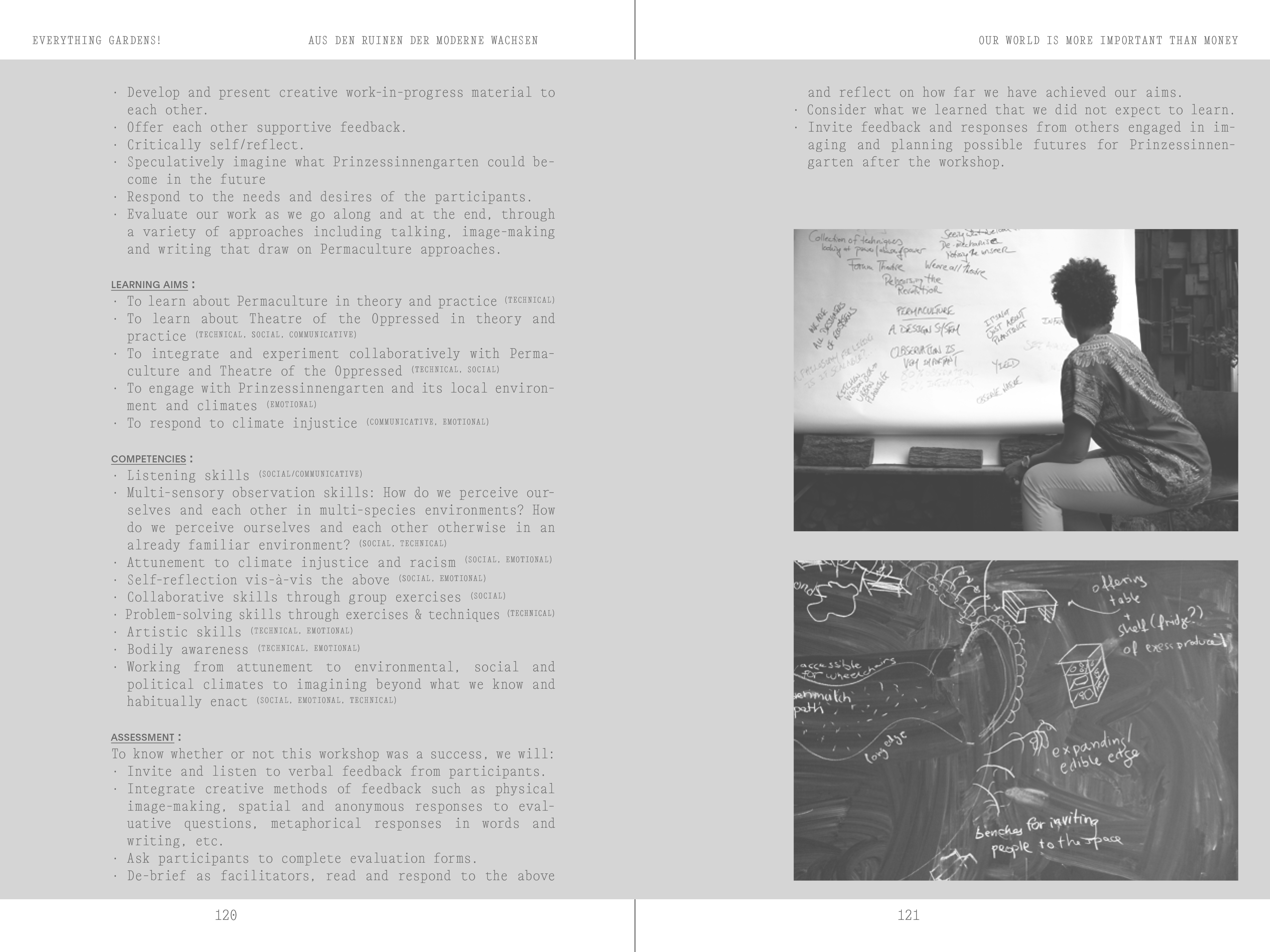

Images above: Page excerpts from the book.

City Country Land

Program 2015Throughout the summer of 2015 the Neighborhood Academy is inviting activists, artists, architects, researchers and representatives of initiatives working on questions of urban and rural resilience, commons, land-politics and social housing. The invited guests, together with partners from Moritzplatz, Kreuzberg and Brandenburg, will work on local issues and exchange experiences and working tools through workshops, walks, interventions and with the help of manuals. Over time, based on the first program in the summer of 2015, an open and jointly build knowledge and experience platform will be formed. It will be complimented through the construction of an experimental architectural structure: a multi-story vertical garden. Starting with a nucleus, the garden architecture will gradually grow through DIY-constructing and evolve to a physical space for the Neighborhood Academy.

→ More about the program and the participants.

Food Futures

Publication. 2015.By Brett Bloom, Marco Clausen,

Bonnie Fortune, and Åsa Sonjasdotter.

→ Download PDF

The continued globalisation of modern food networks is introducing an unprecedented level of complexity to the global food system, bringing both significant benefits and systemic risks. Disruptions at any one point in the system would be likely to reverberate throughout the food supply chain. Volatile food prices and increasing political instability are likely to magnify the impacts of food production shocks, causing a cascade of economic, social and political impacts across the globe.

Food System Shock: The insurance impacts of acute disruption to global food supply, Lloyd’s Emerging Risk Report. 2015.

This publication starts with a simple question born of our own lack of understanding: “What is the future of food in the Berlin-Brandenburg Bioregion?” It turns out to be an extremely difficult question to answer. We are interested in knowing where our food comes from and wanted to learn from people in the city and on the farms what kinds of awareness about food was out there and to talk to people who might have the story of the future of food here. Our investigation had some urgency as it was fueled by the horrifying report quoted above. It paints a gruesome near future with massive climate disruptions, food riots that last for years destroying regional capacities to make food, and large die offs of vulnerable populations of people that have been historically oppressed. The report reads like dystopian science fiction. It is a powerful narrative as it will drive investment, risk assessment, and undoubtedly have an impact on how food is produced around the globe.

How do we begin to contest such disempowering, irresponsible narratives? We could even say it is immoral to advocate the position Lloyd’s—“Lloyd’s is not a company; it’s a market where our members join together as syndicates to insure risks.”—take as the report also projects the attitude that the company will do nothing to mitigate this horrendous future, but will instead seek to profit from its multiple, epic miseries. We are interested in changing the narratives around the future of food. This is an important role for cultural workers to undertake.

A big problem we have had in making this book is that it is difficult to see where to act because it is hard to get an overview let alone have an intuitive or embodied understanding of the scope and scale of the things we are investigating. This publication is a way to get started. We entered into the process with our own personal experiences. This is where we start because it seems that no one has an overview of all the intricacies of the global food system and how it might respond to crisis. A mainstream effort is needed to understand localized food futures—systems that provide for people in a region particularly in the face of massive stresses, disruptions, and breakdown—and how they can work in solidarity and harmony with each other across national or regional boundaries, differences, and ideologies in neighboring regions—in contradistinction to fragile, neoliberal food chains that will easily fall apart. This will need to include all kinds of farming and farmers to get going. Conversations must happen across the varying scales of farming, the techniques used (organic in practice, certified organic, industrial organic, conventional, non-food farming), and the political positions that drive them.

We have been travelling in the areas of Berlin and East Brandenburg. We have met with people engaged in urban gardening: Severin Halder, researcher, garden activist in Allmende-Kontor in Berlin; Gerda Münnich, garden activist; large-scale farmers: Hans Georg von der Marwitz, who also is a politician in the parliament, 800 ha (1977 acres); Lutz und Manfred Wercham, 400 ha (988 acres); mid-size farms: Bienenwerder, 80 ha (198 acres); as well as small-scale farms: Ulrich Vössing and Jennifer Klemin, Hanna and Johannes Erz. From these conversations, we have picked up a few recurring themes. One urgent topic that has repeatedly come up is the need for increased communication between people in the various areas of the region from city, suburb, to country side.

We want to use the concept of the bioregion in order find a way to talk and think differently about food futures in the region. Bioregionalism is conceptually useful as it includes a discussion of biodiversity, communication with processes that are bigger than the region. It is in contradistinction to nationalist identification with land, which becomes impossible once one knows what a bioregion actually is and consists of. In fact, bioregions do not conform to national boundaries and bioregions overlap with one another, exchange things, share with one another. Perhaps bioregionalism is a powerful way to fight the stupidity and shortsightedness of identifying with land instead of locating oneself in an ever changing complexity and diversity.

This publication is a first step. We will organize meetings and exchanges between people in the city and farmers. We will work to expand the conversations and the awarenesses around food futures and the things that effect this struggle in the region.