Cultivating Abundance

Lunds konsthall, 1 June – 25 August 2024.

The combination of plant cultivation and sourced archival material forms the basis of Åsa Sonjasdotter’s artistic practice, which investigates social and ecological relations. In her work, Sonjasdotter reactivates overlooked knowledges of cultivation and demonstrates how the genetic information coded in crops is also a memory bank common to both humans and plants.

The exhibition features three central works by Sonjasdotter, addressing eco-political questions through collaboration with artists, farmers, and researchers from various geographic and social backgrounds.

Cultivating Abundance (2022) is a film that revisits the period, from the 1880s onwards, when industrial farming techniques for breeding monoculture crops were invented at the Swedish Seed Association at Svalöv. The film also lets us follow how the seed association Allkorn retrieves the peasant-bred grains that were lost with this change. In the inner courtyard of Lunds konsthall, Sonjasdotter will build a site-specific highrise bed for the cultivation of crops included in her work.

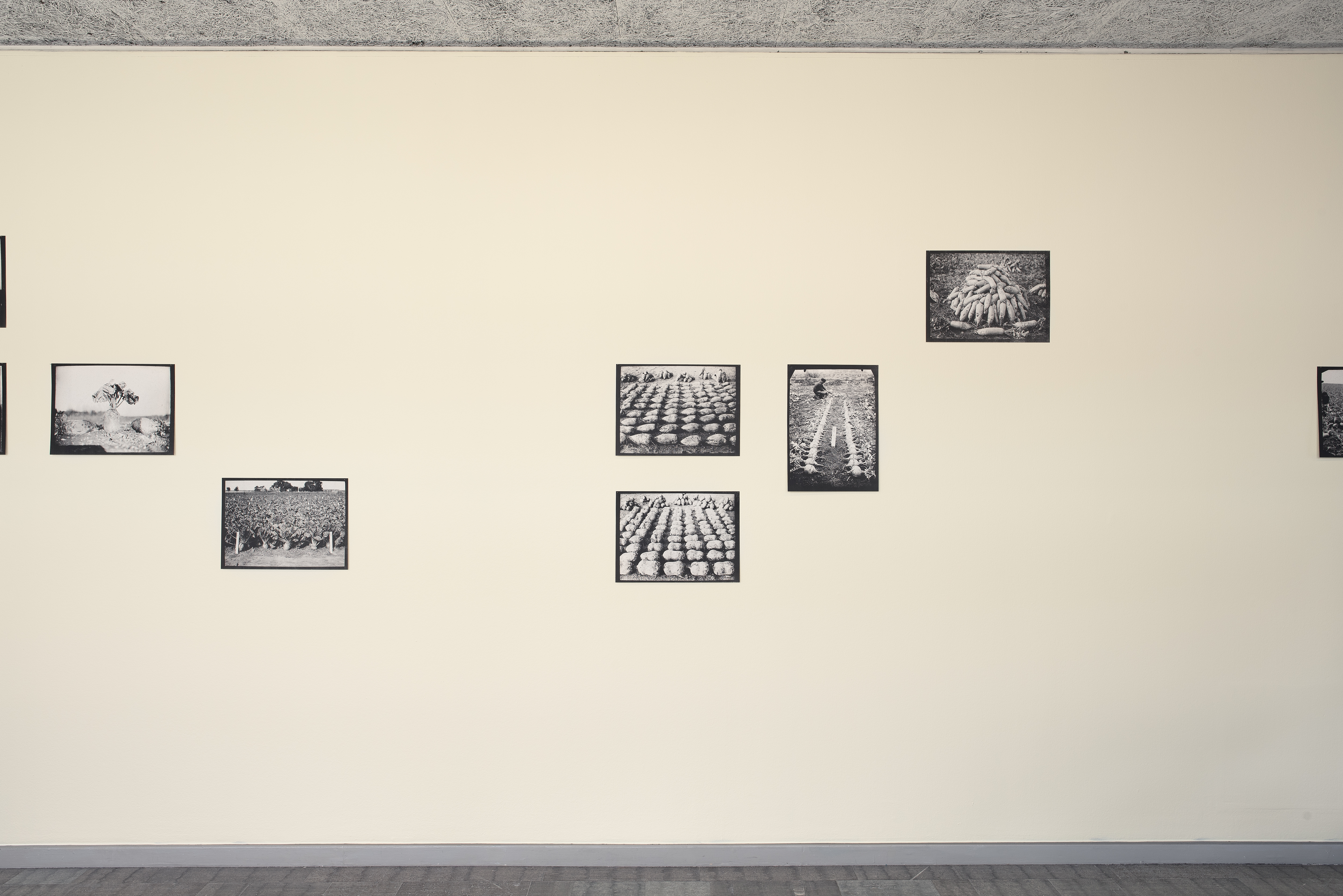

These photographs and films document the process of inventing the technique of plant breeding to produce uniform crops. The development of this method was accompanied by elaborate visual representation of standardised crops and their cultivation through the recently invented technique of photography. This can be seen in the reprints of tsilver gelatin glass negatives from the Swedish Seed Association. Revisiting this decisive moment helps us understand how the monoculture farming industry has gained global scope.

The technique invented was, in the plant breeders’ own words, ‘a total reversal of the traditional understanding’. Instead of saving selected seeds, which since ancient times had been understood as a slow process of adaptation, the breeders at the institute of the Swedish Seed Association worked towards ‘recognising and controlling the uniformity’ of ‘already existing’ properties in the seeds.

The old understanding, which regarded living matter as an ongoing flux, was abandoned. Instead, new ideals were formed in resonance with theories related to hereditary patterns. To make these theories real, selected plants were inbred in several generations until so-called ‘pure lines’ emerged and genetic ‘contaminants’ were removed. From these lines, ‘original elite varieties’ were produced, so that harvests would ‘yield greater sales value’, according to the breeders. In 1961 these requests were gathered into the legal complex of UPOV, The Convention of the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, which is in force in the EU and 76 other nations today.

The invention of uniform monoculture plant breeding provided ‘proof’ and arguments for biopolitical movements propagating the hygienisation of lifeforms. The State Institute for Racial Biology was founded in Uppsala, Sweden, in 1922, a decision motivated by the results at the Swedish Seed Association. These two institutions would become models for ’genetic hygiene’ would create further political incentives for putting them into practice.

Adretta: On Memory as Practice, Potato Breeding, and a Socialist Model Village in the GDR. With Elske Rosenfeld and Mikhail Lylov, 2012–ongoing).

Two different archives are at the heart of this story, told in text and images and by the plant itself. One is the photographic archive of the former Institute for Plant Breeding in Groß Lüsewitz in the German Democratic Republic. The Archive was compiled by photographers employed by the Institute between 1948 and 1990. Its purpose was to document the development of the Institute, as one of the major centres for agricultural research in the Eastern bloc, and of the village itself, as a model village for the industrialisation and urbanisation of agriculture in the GDR. The archive was thrown on a rubbish dump when the Institute was closed down in 1990 and saved by a former employee. It was preserved thanks to the personal efforts of members of the village history club.

The second archive is the potato Adretta, which was developed at the Institute and certified here in 1975. Like all cultivated tubers, Adretta is an archive of a breeding process, a continuous human–plant dialogue, dating back to prehistoric times when agriculture began. Adretta became a success because of its robustness, which suited the needs of the large-scale farming units of the planned economy. It was soon cultivated widely, not only in East Germany, but also around the whole Soviet Union. After 1990 it no longer met the requirements of the new capitalist economy. As an archive, Adretta is fragile. It needs to be replanted each season to survive. But it fared better than the photo archive of Groß Lüsewitz: Adretta has become one of the most beloved and prevalent staples of post-Soviet subsistence farmers from Kazakhstan to Siberia.

In the accompanying pamphlet produced in conjunction with this installation, the two archives – processed through Åsa Sonjasdotter’s and Elske Rosenfeld’s research as hosted by the artist and curator Mikhail Lylov – are enquired as forms of dormant knowledge that are latent or active sources of resistance and dissent. Such knowledge pits itself against a capitalist logic, a way of inscribing human and human-to-non-human relations, that is today proving ever more clearly dysfunctional.

Åsa Sonjasdotter: Cultivating Abundance

Introductiry catalogue text by the curators Laura Goldschmidt and Åsa Nacking.

Åsa Sonjasdotter (born in Helsingborg, Sweden, in 1966) now lives on her family farm on the island of Ven and in Berlin, but she grew up in Lund and therefore has a special connection to the city and its surroundings. The combination of the city with its academic studies and the countryside with its cultivation is significant for her artistic practice. Based on thorough research, it articulates itself through activist working methods that involve local communities.

This groundedness in the real conditions of place also articulated itself for Sonjasdotter’s participation in the group exhibition Public Act at Lunds konsthall in 2005. She established a kind of ‘speakers’ corner’ with a gigantic billboard placed in front of City Hall, where the inhabitants of Lund could express opinions and convey messages directly to their elected representatives. Like back then, her current artistic work departs from acts in public space, but today her focus is the countryside and issues of cultivation.

In the light of notions such as the Anthropocene (humankind’s historical and even geological impact on the planet) and of the urgent crises affecting social life and the climate, Sonjasdotter chooses to engage with what empowers us, mainly rethinking on how to cultivate with the earth. She investigates how agricultural narratives have been shaped and what they have meant for our current living environments and social conditions, asking herself if something was forgotten on the way. To gain relevant insight she focuses on her immediate surroundings and studies its agricultural history.

An important source of reference is the Swedish Seed Association in Svalöv and its archive documenting past experiments with plant breeding techniques, on which modern agriculture and the food industry still rely. Sonjasdotter’s research methodology is based on browsing such archives but goes deeper. Her aim is to gather and disseminate knowledge on ecological and social living conditions, especially within areas that have often been neglected. This collected and processed material has also informed the film Cultivating Abundance, which is featured in the exhibition.

Local research is, in other words, of crucial importance to Sonjasdotter as she addresses the social/democracy- and climate-related challenges we are facing. Some of her works demonstrate direct connections between local initiatives and global politics, anchoring the individual act or gesture in far-reaching issues that concern many more people. This clarifies how making a small difference may leave a large imprint. Even small efforts may contribute a great deal if enough people are affected and become involved.

With this insight Sonjasdotter propagates local knowledge and involvement through building international networks and finding different ways to exchange knowledge about plants and cultivation methods to slow the current deterioration of life webs. Several of her projects are realised in collaboration with other active artists, farmers or researchers within these fields of interest.

In this exhibition we see how a combination of rational and aesthetic fields of knowledge may yield new knowledge/awareness. Sonjasdotter states that our living cultural heritage is the result of a dialogue between humans and plants over many millennia. Some works address complications between them that have occurred relatively recently and urge us to be vigilant when facing the future. In her projects the modern distinction between subject and object breaks down, and she demonstrates that plants are paradigmatic for the inter-connectedness of all living being and the world itself.1

Without the photosynthesis of the plants, which uses sunlight to convert carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and water from the ground into oxygen, there is no life on earth. Therefore plants are not just something growing in nature. They are the air we breathe, the food we eat and the feed we grow. Sonjasdotter’s work articulates how we, if we follow through on this thinking, may find our place in the world thanks to plants, and how we depend on them for our livelihood. This innovative approach has inspired her exhibition, and it redraws classical boundaries between disciplines such as archaeology, art history, biology and agricultural history by emphasising our co-existence with nature and demonstrate that our heritage is equally consisting of nature and culture.

Sonjasdotter’s practice is characterised by free form and the conviction that artistic organisation may lead to real-world change. One expression of this is that the exhibition contains several works realised specifically for Lunds konsthall.

The grain cultivation in the gallery’s inner yard happens in collaboration with the Allkorn association and the Bygga och bo i Lund association. Outside of the gallery Sonjasdotter works together with the Technical Services of the City of Lund and Lund tillsammansodling in the Knowledge Park to cultivate the German potato variant Adretta, along with cultivated and wild kale from Ireland. In addition an excursion to the Källunda farm in the village of Häglinge is being planned, to give interested exhibition visitors a chance to study the work of the Allkorn association. Furthermore, the work The Kale Bed Is So Called Because There Is Always Kale in It was developed in collaboration with the artist and photographer Mercè Torres Ràfols, and the work about the Adretta potato was created in dialogue with the artist and researcher Else Rosenfeld and the artist and curator Mikhail Lylov.

Warm thanks to Åsa Sonjasdotter herself for her invaluable engagement for the exhibition. Thanks also to all who have participated in her collective work processes. Special thanks to Groß Lüssewitz Kultuhistorischer Verein for lending us their archival material on the Adretta potato variant. Thanks also to Lantmännen i Svalöv, Centrum för Näringslivshistoria in Bromma and the Malmö Art Museum for lending archival material. We are also grateful to Allkorn for providing the seeds for the cultivation project in the gallery’s inner yard, to Norika for providing Adretta seed potatoes and to the Irish Seed Savers for providing kale seeds.

Notes

1 See Frédérique Aït-Touati and Nikolaj Schulz, ‘TITLE’, in Emanuele Coccia (ed.): The Life of Plants: A Metaphysic of Mixtures (CITY: Polity Press, 2018), pp.